Eleven years ago, I went on a road trip to the Finger Lakes district of New York with two friends. Happening upon a dusty second-hand bookshop in Ithaca, I discovered a 1919 copy of W. Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence, a novel based on the life of Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin. I’d read the book a number of times before, but the price was a mere six dollars, so how could I pass it up?

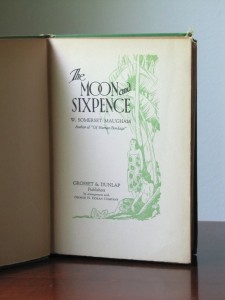

It isn’t a fancy edition by any stretch of the imagination, but in its simple way, it’s a lovely object. I love the bold graphic of the palm trees on the cover and the graceful illustration of the Tahitian beauties on the inside cover. I adore the way the title of the book has been designed, with the linking o‘s in Moon. A fascinating little detail is the embossed publisher’s insignia on the front cover that features a peacock (visible in the bottom right of the photo).

My edition of the book is battered, so it’s not worth any more than I paid for it. One corner has been banged up, water spots speckle the cover, and the edges of the pages have yellowed over time, but this just shows that the book was read and enjoyed by many people over time, as any good book deserves to be. As well, there’s the intriguing inscription, which appears to be as old as the book itself, in well-formed script inside: “Happy Birthday Hugh. Frances.” I can’t help but wonder what Hugh’s relationship to Frances was. Were they siblings? Lovers? Husband and wife? Was she trying to impress him with her good taste in literature? I can’t help but wonder if he liked the book. What happened with the two of them after he received it? There’s a story there that we’ll never know, but we can always invent something.

With old books, the story within the covers is augmented by the story of the book as a physical object, passed from one person to another over time. Of course, there’s a lot of mystery about a book’s previous owners, hinted at only by things like inscriptions, notes in the margins, and passages underlined. And what does such a book say about the time in which it was produced? To me, my copy of The Moon and Sixpence speaks to a more elegant and serious time in which books were considered objects of beauty and thought of as items to be treasured for generations.

I have quite a number of battered volumes that bear the stamp of my grandfather, Jesse Kaiser, a World War One veteran who died when I was just eight years old. I have only vague impressions of him as a kindly but sombre man. Photographs of him, and his collection of books–mostly war-related novels and poetry from the teens and twenties–are just about my only link to him and hint at a preoccupation with events that were undoubtedly burned into his psyche for the rest of his life. Having his books gives me a sense of connection to him and to the past that I wouldn’t otherwise have.

In our world of disposable culture and e-books, hard-copy books have lost the sense of being significant objects in and of themselves, and I think this is a shame. Although I have an e-reader and find it handy for travelling, I still much prefer curling up with something made of paper than with a cold, hard, electronic screen. But I wonder how many people like me still roam the earth. Although I may be a dinosaur, give me my old books with their dog-eared pages and their whiff of the past any day of the week.

Follow

Follow