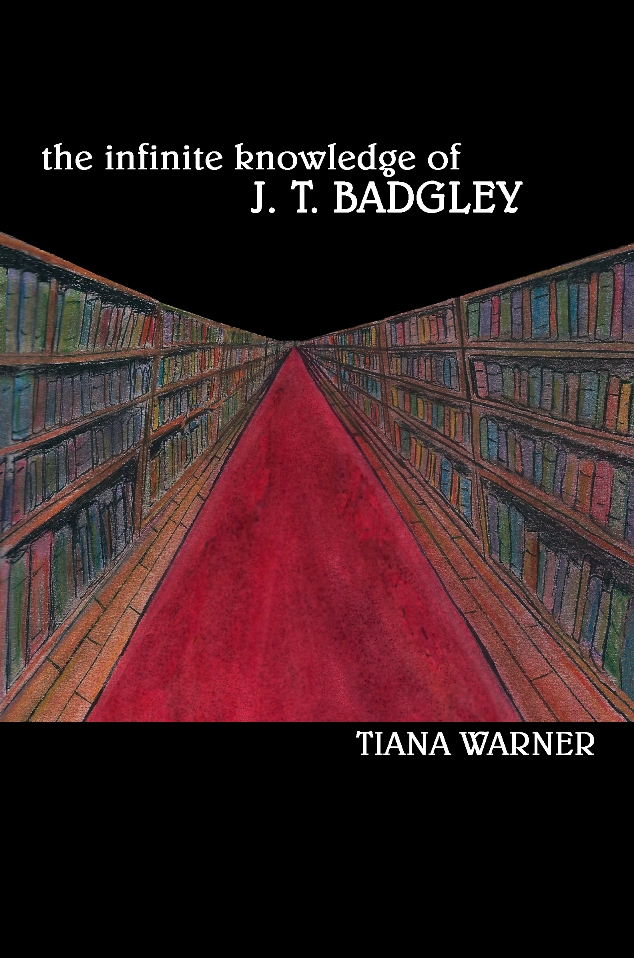

Tiana Warner has just released her first novel, The Infinite Knowledge of J.T. Badgley. The 23-year-old author hails from Abbotsford, BC, and works as a software developer. Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of working with the gracious Tiana on her book, a young adult science fiction novel. But The Infinite Knowledge is really so much more than this genre label suggests. I thoroughly enjoyed chatting with Tiana about her book, and hope you will enjoy our interview.

Tiana Warner has just released her first novel, The Infinite Knowledge of J.T. Badgley. The 23-year-old author hails from Abbotsford, BC, and works as a software developer. Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of working with the gracious Tiana on her book, a young adult science fiction novel. But The Infinite Knowledge is really so much more than this genre label suggests. I thoroughly enjoyed chatting with Tiana about her book, and hope you will enjoy our interview.

CK: What was it that prompted you to start writing The Infinite Knowledge of J.T. Badgley in the first place, and how long did it take you to write the book?

TW: I’ve wanted to be a writer for as long as I can remember. When I was 5 I would write stories and staple the pages together and sell them to relatives. I started writing The Infinite Knowledge near the end of high school, when we studied classics like Gulliver’s Travels and 1984. I knew then that I wanted to write a book with a purpose—so I started with the topics I feel passionate about, and everything else followed. It took me six years because of university, but in the end I’m glad I was patient.

CK: In the book, the unsuspecting protagonist Jake (J.T.) plummets via a portal through space and lands on the planet Zielaarde, a planet very like our own in some ways. Through your portrayal of Zielaarde, what kinds of things were you trying to say about Earth and its inhabitants?

TW: I want the reader to interpret much of it for themselves, but I will say that I had a fun time exploring certain contemporary issues. Some of these issues are more light-hearted, while others I take more seriously and feel strongly about. The inhabitants of Zielaarde often reflect the way we humans regard the environment, technology, and each other.

CK: The book is an excellent read—it’s dramatic and suspenseful, and I wasn’t sure how it would end until it actually did end. As well, it’s often funny—the reactions the Ziels (inhabitants of Zielaarde) and Jake have to each other were quite amusing. But the book is also very thought-provoking and serious. Ultimately, what thoughts or impressions did you hope to leave readers with?

TW: I hope readers come away thinking about said contemporary issues, but I also hope they think about their own roles and abilities in this world. The book is primarily written for teens, so when I was writing it I wanted make sure I avoided telling the reader what to think, and focused on simply provoking them into thinking. Jake faces the same identity-crisis problems that so many teens face around the time of their high school graduations, and he’s at an age where he starts to gain awareness and scepticism of philosophy and religion. He is forced to gain a stronger sense of self in the book, and I hope Jake’s self-exploration also encourages such thinking in the reader.

CK: One thing I enjoyed about the book was your ability to really get inside Jake’s experience. He suffers immensely, and the reader is keenly aware of his every thought, sensation, and emotion. Was it difficult to write in this intense sort of way?

TW: It certainly took more than one draft before I was able to fully portray Jake’s thoughts and emotions. It takes a lot of focus and imagination to pretend you’re an entirely different person in an entirely different place, and then to describe exactly how you feel and what you’re thinking at that moment. I find that it helps to imagine a situation using all of the senses.

It’s interesting when you’ve been pouring out the deep thoughts and emotions of a character for years, and then it comes time to actually let other people read it. It feels too personal, like they’re about to read into part of your soul. I guess that’s how you know you’ve really put everything into a character.

CK: Tell me about your fascination with astronomy and how you’ve brought this into the book.

TW: It’s funny, because when I was a kid I hated learning about space. I was afraid of it and tried to avoid thinking about it, because I couldn’t understand how space and time were even possible. I still can’t understand it. I guess writing this book was a way to overcome that. I pushed my own fear and uncertainty onto Jake. When you pick a topic that you feel very strongly about—whether that feeling is of love or hate or obsession or fear—you write about it more passionately. What strengthened the passion was when I decided to take an introductory astronomy class in my last year of university. It was without a doubt one of the most interesting classes I’ve taken, and also a very sobering one because it makes you realize how small we are in such a vast universe. By the time that class was done I had already written most of The Infinite Knowledge, but I was still able to apply some of the science I learned to the story. It’s fun inventing concepts when you write science fiction, but what’s more fun is when you can relate your made-up concepts to real science.

CK: Your love of animals was really obvious to me in the way you portrayed certain creatures in the book. Can you tell me a bit about this love, and how it informs the book?

TW: There’s never been a time in my life where I’ve been without a pet, and I think a dog will always be my perfect companion. It takes owning a dog or a horse to really understand the bond you can have with one. As Betty White once said, “Animals don’t lie. Animals don’t criticize. If animals have moody days, they handle them better than humans do.” I tried to portray such human-animal friendships in a couple of ways in the book. An important, loyal character doesn’t always need to be a person.

CK: Which writers do you like to read, and which have been most influential on your work?

TW: My favourite author of all time has to be J. K. Rowling. I’m a Harry Potter superfan. In general, I tend to enjoy a wide variety of books and authors, although I mostly find myself reading YA. I wouldn’t say any one writer has influenced my work, though. Everyone has a writing style and I tried to distinguish my own, as well.

CK: Do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

TW: I think a person has to have a certain level of obsessive passion in order to write a full novel, so my advice is “Don’t hold back.” The best part of writing—and especially sci-fi—is that you get the freedom to create whatever you want to create. It’s your book and you control everything inside of it, so do what you want with it! Immerse yourself in your book’s world. Tape outlines and photos and maps to your walls, write down ideas in your cell phone as they come to you, make a playlist that inspires your characters, get those Crayola window crayons and write inspiration on your mirror—whatever it takes for your book to materialize. Then, when you write your first draft, don’t even pause to think about the format or spelling errors. Just let those creative juices fly, and do your editing later.

CK: Are you currently working on another novel? If so, can you tell us anything about it?

TW: I’ve been harbouring an idea for about a year, but haven’t had the chance to give it a good go. I’m very excited about it. It’s different from The Infinite Knowledge, however, and has a more mature theme. That’s all I’m going to say, since I’m still outlining the plot at this point! I’m also trying to convince a friend of a friend to let me write a story based on his very interesting life.

For more information about Tiana Warner and The Infinite Knowledge of J.T. Badgley, please see the author’s website: http://www.tianawarner.com.

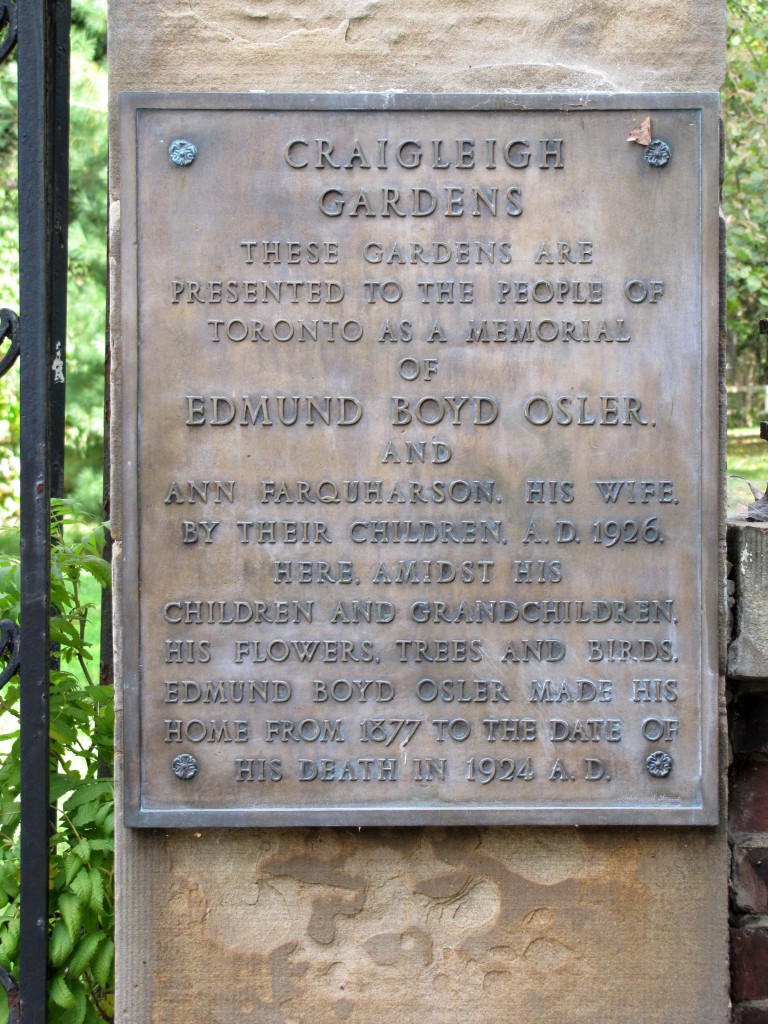

And here’s the plaque that commemorates the Osler family’s extraordinary gift to Torontonians:

And here’s the plaque that commemorates the Osler family’s extraordinary gift to Torontonians: I’m fortunate enough to be able to treat myself to a walk in this lovely park almost every day. It’s airy and spacious, and it’s a wonderful place for my dog Trinka to romp and stomp and enjoy some precious off-leash time.

I’m fortunate enough to be able to treat myself to a walk in this lovely park almost every day. It’s airy and spacious, and it’s a wonderful place for my dog Trinka to romp and stomp and enjoy some precious off-leash time.

Follow

Follow