This blog post originally appeared as an article on this site. Although most self-publishing authors now understand the value of having their manuscript edited, this wasn’t the case a few years ago. If you’re a writer who’s wondering how necessary professional editing is, please read on.

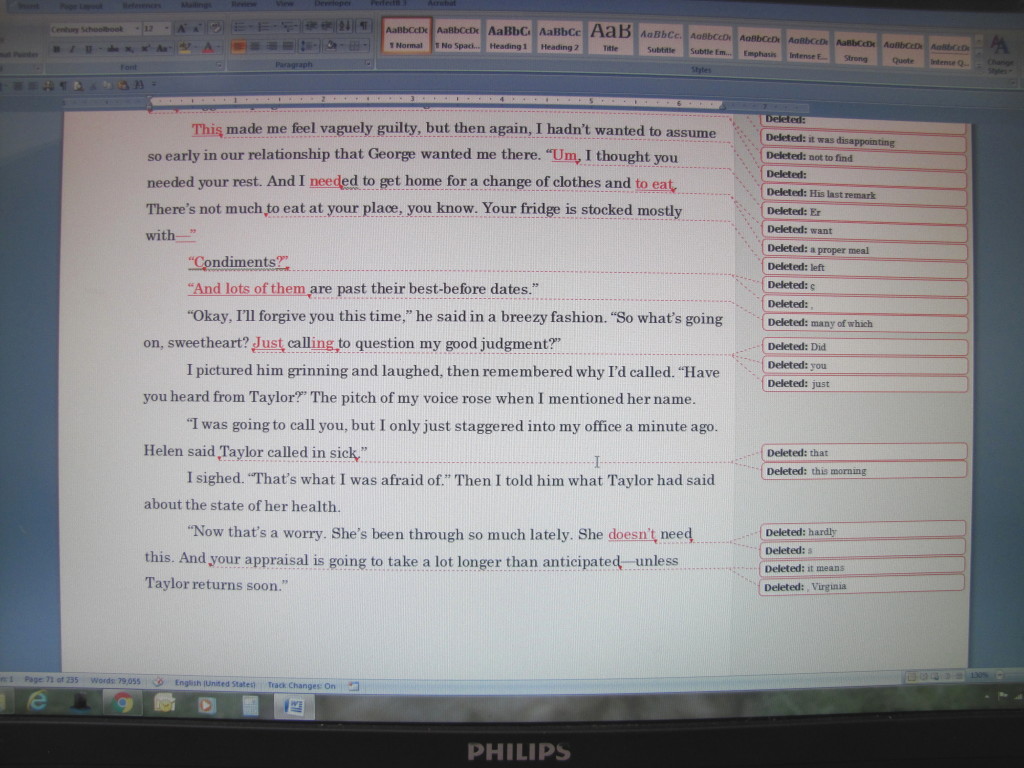

It’s a fact: writers need to have their work professionally edited. If you’ve spent countless hours writing and rewriting your novel, you’re much too close to your work and have probably read it so many times that you’ll overlook even the most basic typos. You’ve gone word blind.

But real editing goes well beyond simply knowing how to use spell-check to catch typos, and unless you’re an editor, you won’t be aware of all the types of errors you should be looking for. Although you may be tempted to get your cousin who majored in English Lit fifteen years ago to edit your work, you should instead hire a trained professional who can shape and polish your work to publishable standards. Your work deserves nothing less.

Here are some important reasons to get your work professionally edited: consistency, conciseness, and clarity.

Consistency

You’re probably unaware of the myriad ways in which an editor maintains consistency across the board. Without consistency, discerning readers will be distracted from your content by bothersome little errors. Worse, inconsistencies often cause readers to scratch their heads in confusion. So much for clarity! This example illustrates just a few of the types of inconsistencies that editors look for.

Marion selected her favorite dress, which was a beautiful colour—blue, to match her eyes. To go with it, she picked out black sandals, a crimson cashmere scarf, and a nutmeg-brown hand-bag. The handbag was a present she’d received from her erstwhile fiancé, Edmond J. Babcock. Edmond was a mover and shaker in the fashion business, and he’d given her a number of designer hand bags over the years. She enumerated them: 1 red, three brown, and 5 blue. Then there was that huge moss-green bag that he had matched precisely to the color of Marianne’s eyes.

Did you catch the inconsistencies?

- The sample contains both American and Canadian spelling—favorite and colour. And to make matters worse, colour is spelled a second time in the American way (color). Keeping in mind the market for their book, the author needs to decide whether to use Canadian or American spelling.

- The word handbag is treated three ways: as one word, as a hyphenated word, and as two words.

- Numbers are sometimes spelled out (three) and sometimes written as numerals (1).

- Most troubling of all is the Marion and Marianne problem. Given the author’s general sloppiness, we might assume the two are one and the same person. Then again, there could be two characters here, as one has blue eyes and the other has green. Or has the author simply been careless enough to allow Marion’s blue eyes to morph to green? (You’d be surprised by how often this occurs.) Would Edmond really be dumb enough to give Marion a handbag the colour of Marianne’seyes? (If so, this could explain why he’s an erstwhile fiancé.) You can see the confusion that a few small inconsistencies cause. All this can be sorted out only by querying the author about their intentions, which is what a professional editor will do.

Conciseness

It’s all too easy to fall in love with words, and some writers think that the bigger the words, the better. If you pepper your prose with lots of fancy adjectives and adverbs and throw in wordy phrases, won’t that will make your writing more sophisticated? Usually not. More often than not, readers will feel lost in the Land of Verbosity and may need a machete to hack their way through to any clear understanding of what you have to say. At best, wordiness slows readers down. At worst, it makes them grow exasperated and impatient as they wrack their brains to decipher the intended meaning. They may ultimately lose the battle and toss the book aside. Never sacrifice clarity for the chance to throw around pretentious words and impressive-sounding phrases. Nothing is more important than clear communication, and it is the editor’s job to unearth the meaning hidden in wordy manuscripts by removing all that clutter.

Here’s an example of wordiness extraordinaire:

Alfred, who was a distinguished professor of note who prided himself, for the most part (although he had lapses) on his perfectionistic, meticulous, careful, persnickety, detail-oriented attention to the finer points of domestic science, in modern times known as housekeeping or even housework, had, as a matter of fact, just this morning detected, much to his horror, the presence of a beetle, which appeared to be of the ladybug type, crawling in his breakfast cereal, which this morning was granola.

Here’s my version, which I’ve edited for wordiness:

This morning, Alfred, a distinguished professor and mostly meticulous housekeeper, was horrified to find a ladybug in his granola.

That was pretty easy to understand, wasn’t it? No meaning has been sacrificed.

Clarity

You’ve already seen examples of how clarity has been lost when the author hasn’t been consistent or concise. There are endless ways in which authors can create great clouds of confusion in readers’ heads. Here are just a couple of examples:

Hiking staff in hand, Fred’s head was set firmly on the road ahead.

Oh dear. You can be forgiven for thinking that Fred’s head has somehow sprouted a hand that is carrying a hiking staff, for this is what the writer seems to be telling us. In fact, Fred himself is carrying the staff. This is a classic example of a dangling modifier, in which the initial phrase attaches incorrectly to what follows it. Fiction manuscripts are often littered with dangling modifiers; the result is often bizarre imagery and unintentional humour. We have an added problem here as well, for apparently Fred’s head is also on the road while he carries his walking stick, which is highly unlikely. The writer surely means that Fred’s gaze is focused on the road. This example could be corrected as follows:

Hiking staff in hand, Fred stared at the road ahead.

Another surefire way to confuse your readers is to fail to identify clearly what you mean by words like it and this. Editors identify this as an unclear pronoun antecedent error. Here’s an example:

Tony poured the Cabernet Sauvignon in happy anticipation of Cynthia’s arrival. She burst through the door, her purse stuffed with a yappy, writhing chihuahua. Later he would reflect with considerable disappointment that it hadn’t tasted at all like he’d expected it to.

Has Cynthia’s dog been the unfortunate victim of Tony’s carnivorous urges? Or is Tony merely disappointed in the wine? The odds are good that the writer is talking about the wine in that last sentence, but if he’s given to black humour, the “it” could refer to the dog. We really can’t know for sure without querying the author.

The three Cs—consistency, conciseness, and clarity—are just some of the essentials that an editor addresses. Unless these issues are taken care of, a manuscript can suffer from mind-boggling verbosity and confusing constructions that cause readers to give up in frustration. A professional edit will ensure that the message is clear and comprehensible, thereby allowing the writer to reach the intended audience.

Follow

Follow